In the previous post, we had a look at different ways of testing microservices and learned that classical testing methods might not work well in distributed environments.

To recap, testing services in isolation with mocks is fast and cheap but not reliable. Once we change the API of a service, we have to make sure we update the tests in all of its clients. Essentially, service mocks only assume how the real counterpart should behave and the only thing that verifies this assumption is us, humans. Therefore it’s very easy for mistakes to creep in.

Spinning up two services to test the integration between them seems like the next logical step. As we saw in the previous post, this approach is definitely more reliable compared to testing with mocks but it’s also slower and takes more effort to maintain. A service can have many clients, increasing the time it takes to verify a single change. In addition, if we want to deploy our services independently of others, we have to test for backwards compatibility with services already deployed to production. The same is true if we were to spin up all of our services and performed end-to-end testing. Lots moving parts can make our tests flaky and we run the risk of becoming a victim of normalization of deviance.

This post is about a consumer driven contract testing and how it promises to alleviate some of the difficulties in testing microservices.

Consumer Driven Contract Testing

Consumer driven contract testing is a method of verifying that services (e.g. API consumer and an API provider) speak the same language. By providing examples, API consumers set expectations on providers on how they should behave on specific inputs. A set of expectations forms a contract that’s produced by consumers and is shared with providers.

Contract obligations are verified by providers with tests that can be run in isolation, without having to set up integration testing environments. That lets them evolve independently and get immediate feedback during build time when they’ve broken any of their API consumers. Contract testing can be used anywhere where you have two services that need to communicate with each other but becomes especially useful in environments with many services (e.g. microservice architecture).

Pact

Pact is a consumer driven contract testing tool originally written by a development team at realestate.com.au. By enabling services to enter into a contract on how to communicate with each other, Pact plays the role of an authority that ensures both sides honour the agreement. In Pact terminology, a contract is referred to as a pact.

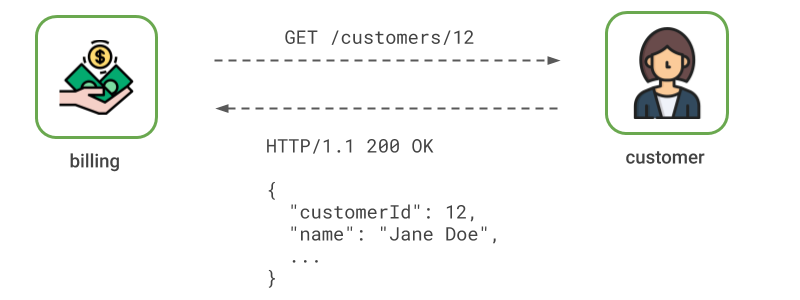

What makes it consumer-driven is the fact that a client of an API has to first describe how the API provider should behave. In the previous post we looked at an example scenario where we had a Billing service and a Customer service. To recap, the Customer service provides an API that the Billing service needs to consume in order to perform billing.

Let’s have a look at how to use consumer driven contract testing in this scenario.

Setting expectations and generating a pact file

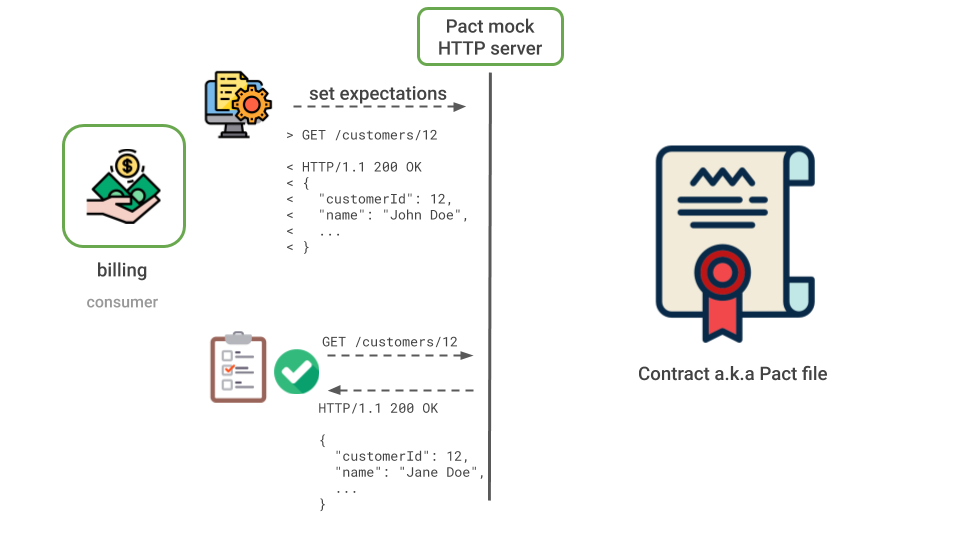

Since the Billing service is consuming an API, it should start setting expectations on the Customer service.

Contract expectations are set by examples and to do that, we need to write some code.

Using a DSL we need to define the interactions that should happen between the two services.

For instance, when the Billing service sends an HTTP GET request to /customers/12, the Customer service should respond with HTTP 200 and with the customer data belonging to the given customer.

Now that the interactions between Billing and Customer service have been defined, we need to exercise Billing service’s code to verify that it actually makes the requests that were defined as part of the contract. To do that, we need to write what essentially look like regular unit tests that test the code that is responsible for communicating with the Customer service. But instead of sending requests to a real Customer service (i.e. an integration test), Pact starts up a mock HTTP server that intercepts all traffic and records it.

If an incoming request is found in the set of interactions we defined previously, the mock server will respond accordingly. On the other hand, when the Billing service makes a request that is either slightly different or completely missing, the test will fail, indicating that the consumer did something that was not defined in the contract.

A collection of these interactions are encoded into a JSON document called a pact file.

{

"consumer": {

"name": "billing"

},

"provider": {

"name": "customer"

},

"interactions": [

{

"description": "fetch customer",

"request": {

"method": "GET",

"path": "/customers/12",

},

"response": {

"status": 200,

"headers": {

"Content-Type": "application/json"

},

"body": {

"customerId": 12,

"name": "John Doe"

}

}

}

]

}

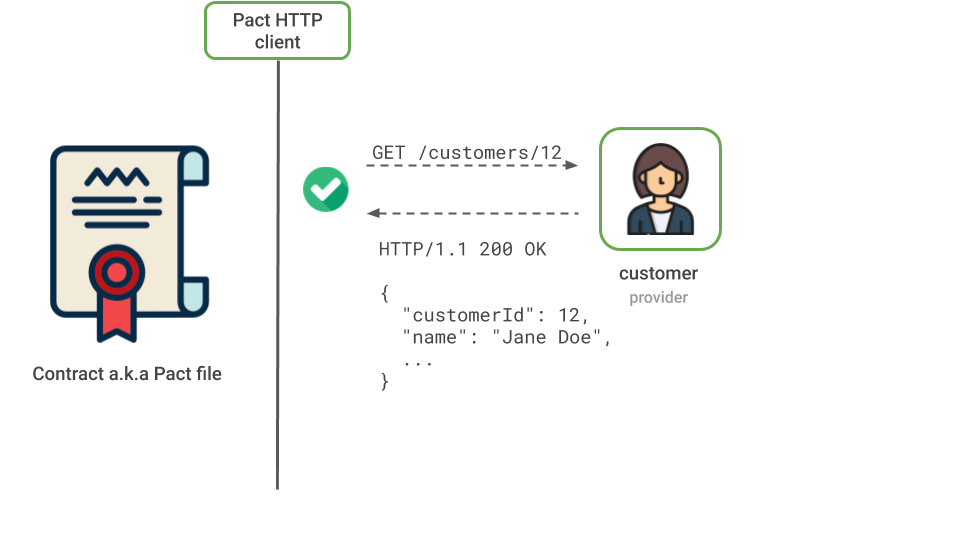

Pact verification

When a consumer of an API has defined a contract and ensured that it complies with it, it is time for the provider side of an API to verify it. The goal of the verification process is to understand whether the provider behaves as described in the contract. To do that we need to start up the provider and give it a pact file. Pact framework starts up an HTTP client that reads all the requests from the pact file and plays them against a running instance of the Customer service. Then it observes how the Customer service behaves and compares the HTTP responses to the ones in the pact file. If they don’t match, the verification will fail and Customer service is deemed not compatible with Billing service.

Looking at the bigger picture, Pact allowed us to verify whether Customer and Billing service speak the same language without having to spin up both services and writing classical integration tests. This greatly improves the autonomy of API providers. Teams responsible of services don’t have to explicitly track how other services consume them. If one of these tests break, the provider team is immediately aware which consumers are impacted. Now they can start a discussion with the consumer team around whether to create a breaking change or come up with a solution that is backwards compatible.

In Building Microservices, the author Sam Newman had the following to say about consumer-driven contracts.

They [CDCs] become the codification of a set of discussions about what a service API should look like, and when they break, they become a trigger point to have conversations about how that API should evolve.

Summary

Consumer driven contract testing helps us decouple consumers and providers in space and time. We don’t have to spin up both services and run integration tests anymore. We don’t even have to care about their version numbers. As long as both sides honour the contract, we can be sure that they speak the same language and we haven’t introduced any breaking changes.

CDCT provides teams more autonomy in how they evolve their API. When the contract has been breached, teams are immediately aware of it and can start a discussion around how to solve the issues before anything is deployed to production.

This post covered CDCT on a high level and intentionally left out implementation details. In the next post we’re going to look at how to build a rock-solid consumer driven contract testing workflow with Pact that helps you remain backwards compatible, automatically find out when contract verification fails and stop you from deploying to production when there’s an incompatibility between consumers and providers.