Whether you’re a new to Spring Framework or have been using it for some time, you’re probably familiar with one of it’s most notable features—dependency injection. Nearly all Spring projects that I have worked with make heavy use of field injection, that is using @Autowired/@Inject annotation on an instance field. I guess this is a popular approach because it is concise and reads well. But have you ever considered the downsides of field injection?

What downsides?

If you’re wondering what downsides I’m referring to, then you’re like me. Let me explain.

I used to use Spring’s field injection all the time. Although I was well aware that Spring framework supports constructor and setter injection, I did not consider using them. There were multiple reasons. But mainly I liked the brevity of adding @Autowired or @Inject annotation to a private field. Spring Framework would do the heavy lifting. Required dependencies were injected to instances of classes without me having to do much work at all. That’s what frameworks are supposed to do, right? To save us from doing the ugly work.

New classes started out small. Maybe they had one or two dependencies but not more than that. Over time though, like in many code bases, classes started to grow larger. And the larger the class, the more dependencies it had. Spring makes it quite convenient. Just autowire them. This process continued until, lo and behold, I realized I had created a monolith. But that’s normal? Right? Raise your hand if you’ve seen a service class with ten or more dependencies with no single responsibility.

Large classes aren’t the fault of field injection

Of course, field injection is not the reason why classes grow too large. On the whole, I guess it comes down to bad programming practices. But I think field injection can contribute to it. I see this happening especially in many Spring applications.

I’m sure you’ve seen this before. Let’s imagine a Spring application with an Invoice entity. An entity class is not useful unless you have a way to persist it. Therefore our imaginary Spring app has an InvoiceRepository. Where do we put our business logic? Let’s create an InvoiceService. What usually ends up happening is that everything that is slightly related to invoices is implemented in InvoiceService and the service class grows out of hand.

Field injection only amplifies that in my opinion. It takes away the pain of introducing a new dependency. I’m not saying that programming should be painful but autowiring a new field is so easy that we stop thinking about whether we should actually do it.

So, is there anything else?

The fact that a class can grow out of hand if we autowire too much collaborators into a single class is, of course, a weak argument against field injection. Good discipline can prevent issues like that. So is there anything else?

As Oliver Gierke put in his blog, using field injection is begging for NullPointerExceptions to happen. Say you create an instance of your class without a DI container. You don’t know, without looking at the source, which dependencies are needed for the class to behave correctly. So it’s just a matter of time until you call a method which in turn calls a dependency that is not initialized. He argues that dependencies need to be communicated publically.

The problem with field injection is that you are allowed to instantiate a class in an invalid state. The class does not enforce invariants. I personally feel that objects should be ready to be worked with after construction. Everything the object needs to do its job should be provided via the constructor. If the object needs a dependency to behave correctly, it seems only logical that it publicly advertises it as one of the required constructor parameters. It’s like making a promise. As long as you provide me the required tools to work with, I make sure the job is done.

In Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests, the authors Steve Freeman & Nat Price have this to say:

Partially creating an object and then finishing it off by setting properties is brittle because the programmer has to remember to set all the dependencies. When the object changes to add new dependencies, the existing client code will still compile even though it no longer constructs a valid instance. At best this will cause a

NullPointerException, at worst it will fail misleadingly.

If we’re talking about the Spring Framework, you might be thinking that there’s no need to instantiate Spring beans manually. More on that later.

To hide or expose dependencies?

When you use field injection, you’re essentially hiding dependencies. Without looking at the source code, you don’t really know what collaborators a class needs when you instantiate it. This job is left for the DI container. Now, whether this is a good thing or not, is another question.

I’m going to reference Code Complete. Steve McConnell wrote the following on formalizing class contracts.

At a more detailed level, thinking of each class’s interface as a contract with the rest of the program can yield good insights. Typically, the contract is something like “If you promise to provide data x, y and z and you promise they’ll have characteristics a, b and c, I promise to perform operations 1, 2 and 3 within constraints 8, 9 and 10.” The promises the clients of the class make to the class are typically called “preconditions,” and the promises the object makes to its clients are called the “postconditions.”

If you think of a contract of any kind, I’m 100% sure that you agree that it should clearly state the responsibilities of all the parties involved. When we take this metaphor to class design, the contract should declare what the class needs from the client and what the class promises to the client. As part of the contract, the client needs to know what collaborators the class needs to fill its promises. For that reason dependencies should be communicated publicly.

On the other hand, maybe collaborators are just an implementation detail and the calling code should not know anything about them? Does dependency injection break encapsulation?. I guess this is a more wider topic which I don’t want to touch in this article.

Constructor gets awkwardly big

Let’s say you decide to refactor a class to use constructor injection instead. To make it more challenging, suppose that you chose a class that has ten or more dependencies. You’ll quickly realize that using constructor injection would create a considerable amount of boilerplate code and in the end the constructor looks uncomfortably massive. It would be very difficult to remember the order of the parameters that need to be passed to the constructor. And above all, it just looks ugly. Field injection seems much easier, doesn’t it?

The fact that a constructor is big is actually a good thing. Well, kind of. This is a clear indication that your class has probably too many responsibilities. Robert C. Martin (a.k.a Uncle Bob) has said the following

A class should have only one reason to change

Meaning that if a class as multiple responsibilities, it also has multiple reasons to change. And that is clear a violation of the Single Responsibility Principle. Field injection makes it very easy to add new dependencies. At the same time, it makes it very easy to grow your class until it becomes a god object.

You want to really cure the pain, not blindly apply pain killers to it, don’t you?

Steve McConnell, in his book Code Complete, mentions low-to-medium fan-out as a desirable characteristic of a design.

Low-to-medium fan-out means having a given class use a low-to-medium number of other classes. High fan-out (more than about seven) indicates that a class uses a large number of other classes and may therefore be overly complex.

Seeing a big constructor is a sign that your class has too many collaborators and it is a good opportunity to think about splitting the class into smaller pieces. Arguably, field injection does not give you a visual cue that a class might be overly complex. Of course, experience, good developer discipline and potentially static analysis tools could remedy this situation as well.

Declaring instance fields final

In his book Effective Java, Joshua Bloch recommends to favor immutable classes.

Classes should be immutable unless there’s a very good reason to make them mutable….If a class cannot be made immutable, limit its mutability as much as possible.

In Java, we usually achieve immutability by not providing setters and declaring fields with the final keyword. In Spring, however, we usually don’t care about immutability because nearly all Spring beans are singletons with no real state (except the injected dependencies) and, most of the time, we know that we should not mutate a Spring bean. Setters are only provided for optional dependencies.

But I think there’s still a benefit from using the final keyword in your Spring beans. Readers of the class can clearly distinguish between mandatory (final) and optional dependencies (non-final).

When we use field injection, we are required that our instance fields are non-final. We cannot declare our private fields to be final and not initialize them in the construction. This would result in a compiler error saying that a variable might not have been initialized.

Testing

You may be thinking that you will never have the need to instantiate your application classes yourself. Therefore you cannot accidentally create an object in an invalid state. The DI container will make sure all the required collaborators are injected. After all, frameworks should make our lives easier. I think this is a completely valid argument. In the end, the classes you’re designing are probably never used outside of the application you’re working on.

This leads us to my next topic—testing. How will you provide mocked dependencies in unit tests when field injection is used?. I have seen that in this case reflection is used a lot to assign values to private fields. Come to think of it, doesn’t this seem like a workaround? What if a class was designed with constructor injection in mind? Then you would be able to create a new instance of a class and pass in the required mocks. No need to perform magic with reflection. It’s as if the class was designed to be testable.

Reducing boilerplate

You have to add additional lines of code to replace field injection with constructor injection. Java is considered a verbose language already, so why bother adding the extra weight?

Firstly, constructors are an integral part of the language. I think it’s completely fine to include a constructor in a class. But I do agree that a large constructor looks like it should not belong there. Which leads me to my next point. If a constructor is too big, take a step back and examine your class from a higher level. Ask yourself, is the class overly complex perhaps? Does it violate the single responsibility principle? Could I split the class into smaller ones?

If your answer to those questions was “no”, then read further. There’s a couple of tricks which you can use to remedy the ugly looking constructor. As of Spring 4.3, implicit constructor injection for single-constructor classes is available. This means that there’s no need to provide @Autowired/@Inject annotations on constructors. And if you’re a fan of Lombok and code generation in general, you could use the @RequiredArgsConstructor to generate a constructor for all your final fields. Of course this implies you use the final keyword for all your required dependencies.

Where the industry is moving?

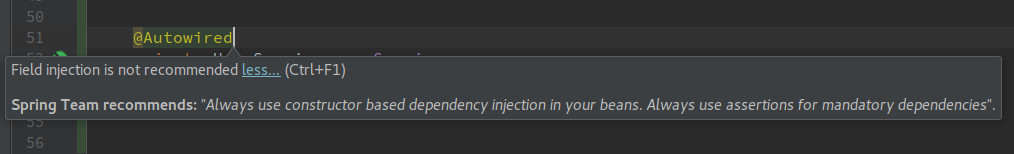

Maybe it’s my confirmation bias at play here but I have seen the theme of favoring constructor injection popping up in many places. At first I started to notice that IntelliJ IDEA began to display warnings if I was using field injection.

It says that the Spring team recommends to use constructor injection instead. Out of curiosity, I scanned through Spring’s reference manual and found the following section.

The Spring team generally advocates constructor injection as it enables one to implement application components as immutable objects and to ensure that required dependencies are not

null. Furthermore constructor-injected components are always returned to client (calling) code in a fully initialized state. As a side note, a large number of constructor arguments is a bad code smell, implying that the class likely has too many responsibilities and should be refactored to better address proper separation of concerns.

In the release notes of JHipster 4.0.0, an application generator for creating Spring Boot + Angular projects, we can find that they have moved away from field-based injection as well.

JHipster is a complete upgrade of Spring libraries, with some major refactoring. The most important one is our switch from field-based injection to constructor-based injection.

One of the reasons for the change is pointed out to be the following.

Constructor-based injection is considered cleaner by many people, in particular as it eases testing

Summary

I have this impression that field injection has become the de facto way to inject dependencies in Spring applications and we don’t even consider the alternatives. But maybe it’s just me. Maybe I have encountered a bad set of projects where constructor injection has been avoided.

The goal of this post was not to persuade you to convert your application to use constructor injection but to make you aware of the benefits that constructor injection provides. Arguably, it makes testing easier and a large constructor, in most cases, is an indication of a violation of the single responsibility principle.

I know the world is not black and white. For some of you field injection is a completely fine method of injecting dependencies and constructor injection could be considered a purist way of thinking. Real life is far from pure and at the end of the day, what’s most important is getting the job done.

Don’t be a cargo cult programmer. Understand the pros and cons and use what works for you in your particular situation.